I think that, for the first time in my life, I have a concrete notion of what it would take to get to AGI. While I’ve been a skeptic of the scaling up approach, I’ve also been skeptical of other people that say “yeah just scaling up won’t work but we’ll probably still get AGI in the next 10-15 years”. I thought it was fairly ridiculous to say this when there is no existence proof (for general intelligence in silicon), and no one even has a concrete notion of what characterizes AGI.

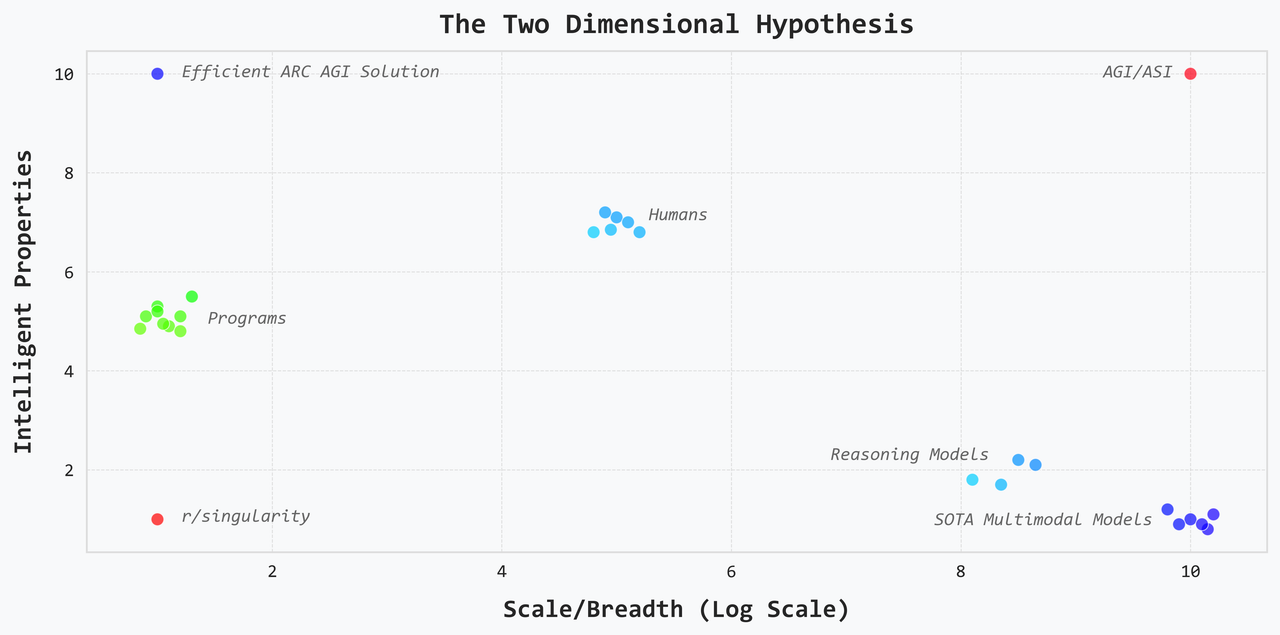

The Two Dimensional Hypothesis

Here is my notion. Intelligence is the combination of intelligent properties and scale or really breadth. There are all sorts of properties that we think are important for making smart decisions. Depending on the problem, we embed some subset of them into programs i.e. code. For example, we leverage systems modeling to make feedback controllers for robots. We leverage search and evaluation to make classical chess engines. But these programs are still narrow: they have intelligence but only in a specific sense and a specific domain. The state of the art (SOTA) multimodal models have the opposite problem. They’re missing many of the intelligent properties that we manually encode into programs. This makes them inefficient, brittle, and suboptimal, but they are still incredibly capable and knowledgeable across a very wide variety of domains.

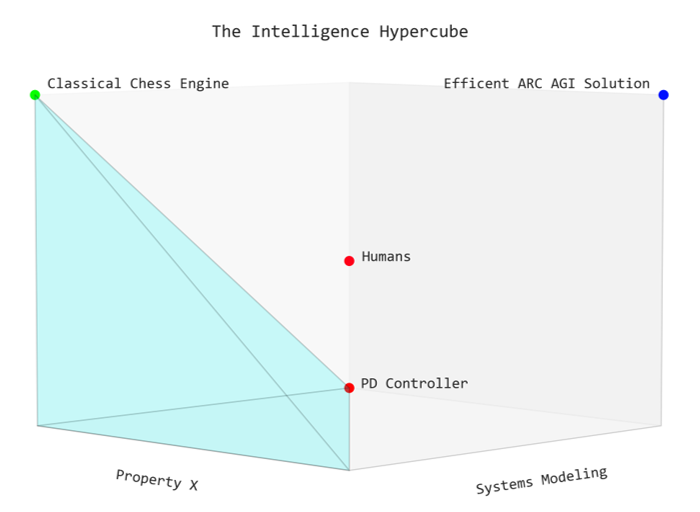

The Intelligence Hypercube

Alright, let’s dig into this a little bit more. While I present this graph as a two dimensional space, intelligent properties are actually themselves a multidimensional space. The different properties are both distinct and independent: going back to the example of feedback controllers and chess engines, we have managed to imbue different intelligent properties and to have high levels of them — but not at the same time. After all, feedback controllers are better than humans at modeling, and chess engines are better than humans at search. What sets humans apart is that we have all of these capabilities at the same time. Thus a good model of intelligent properties is the standard simplex.

We are able to embed multiple properties into the same program, but there is a tradeoff, and this tradeoff manifests in two ways. Gaining more of another property means that you have to divert some compute and add some conceptual complexity. Both of these are key bottlenecks that prevent human written programs for achieving the holy grail: the outer vertex of the intelligence hypercube. Note that humans are also outside the simplex: this means that we are able to transcend the tradeoff even though we are not as capable as narrow programs in any individual property.

This is why a benchmark like ARC AGI is difficult: it requires multiple intelligent properties, and while we have written programs to achieve extreme performance in, for example, search, search by itself is not enough to solve the benchmark. Ok, that sounds fine, but why do I think that an efficient solution will actually reach the outer vertex. It’s the same reason computers are better at brute force search than humans: they just have more resources like memory and processing cores. It’s also why I equated AGI and ASI: if there is a silicon general intelligence, then it’ll have a compute advantage over our biological brains, and it’ll be more intelligent than humans. I really don’t see how you could possibly get AGI without it being also being an ASI.

Jagged Performance isn’t Jagged Intelligence

Ok, let’s also take a look at the SOTA multimodal systems. One popular notion about these models is that they have jagged intelligence — maybe even jagged superintelligence. The idea is that while these models are remarkably general, they are not equally good at all domains. They are better than humans at some domains e.g. history while much worse in other domains like reasoning about the physical world. I believe that this notion is wrong. It is not that these models have different levels of knowledge depending on the domain: rather it’s that the intelligent properties are more or less critical depending on the domain. In some domains — particularly in those with lots of disjoint pieces of information — missing the intelligent properties is not such a big deal. In other domains — particularly those with lots of structure and related pieces of information — missing the intelligent properties is crippling.

Let’s take the most common example of reasoning about the physical world. The conventional wisdom is that SOTA models just don’t have enough knowledge about the physical world because it doesn’t show up enough in the training data. I think what this view misses is that there’s very little to know about the real world: there’s very little information (both in the colloquial and statistical sense of the word information) you need for the physical world because there is so much structure. The problem is less a lack of data and more so a lack of the intelligent properties required to make good use of the available data.

Caveat: now it might still be the case that vision language models don’t quite have enough data about real world physics in their training corpus, but video generation models definitely have enough, and it seems pretty apparent that they’re still missing something crucial.

One particularly important property for the physical world is abstraction. For example, all of the fantastically complicated mechanical creations of humanity are built on a small number of simple machines. Humans see the structure and similarity in this — whether at a vaguer intuitive level for ordinary people or a more concrete explicit level for engineers and builders.

The Implications

Alright, that’s my view on what the search space looks like. Let’s talk about the implications.

Looking Back

All of the work in the last, say, 5 or even 10 years of work in machine learning have been about moving along the x-axis. New methods were definitely created over these 10 years, but they were fundamentally about making better use of more data, and going further along the scaling axis. And real progress was made: scaling up these models from ImageNet to vanilla LLMs to diffusion models and multimodal models did unlock real differences in performance. And I should say that some level of the intelligent properties were gained along the way. But these were gained through relatively weak pressures that incentivized some compression — some discovering of structure. This was never the real focus, and in a both real and metaphorical sense, the regularization weights were quite low because you couldn’t scale up with good performance otherwise. The more recent reasoning models like the OpenAI o series have unlocked a bit of the intelligent properties, but the early indication is that this has come at the cost of some of the models’ scale i.e. they’ve lost some of the information they used to know, and the new intelligent abilities don’t apply equally to all domains since the training is focused on areas like math and code.

I believe that we have reached maximum scale and maximum breadth. It does not seem like there is more knowledge or information to gain, and it does not seem like there is a way to do that either. I think there is some acceptance of this in the industry: for example, Ilya Sutskever has said, “We’ve achieved peak data, and there’ll be no more”. The next goal for these labs is agentic models, and I also don’t think that’s a bad target to work towards (from a research perspective that is — I think the way they’re rushing towards deployment is a horrible idea).

Looking Forward

But I think for real progress, a more big picture vision is necessary. I think there’s a few possible perspectives, and each of them suggests a different path, but regardless, we must a chart a new path to actually get to AGI.

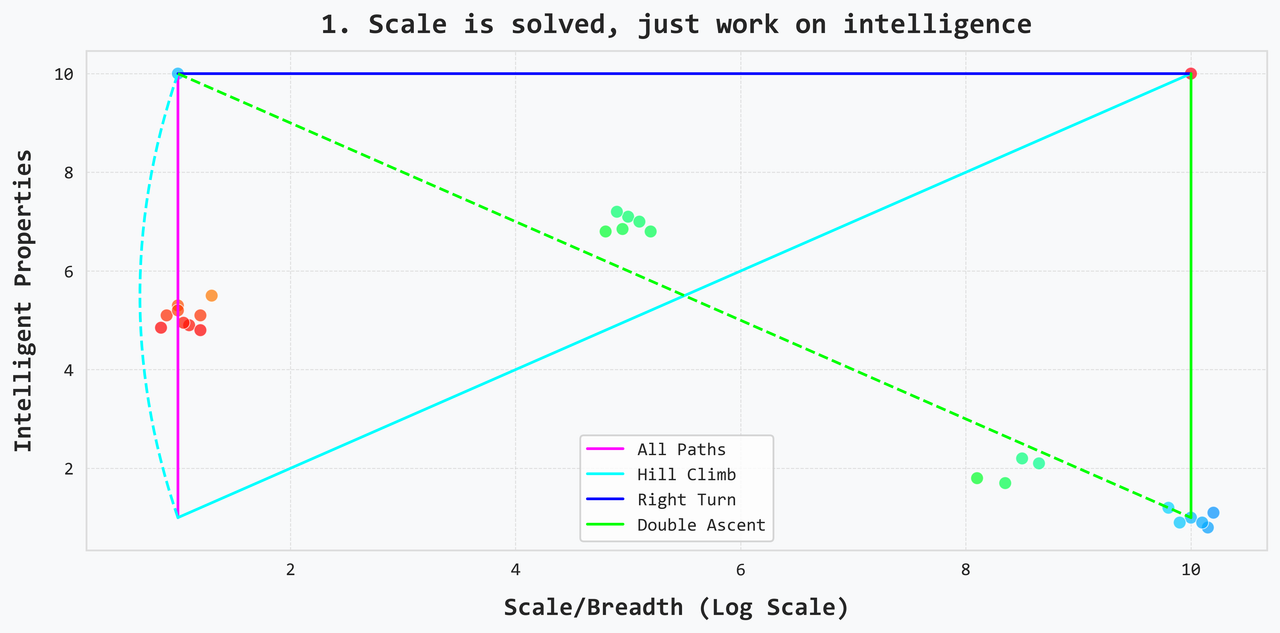

1. Scale is solved, just work on intelligence

This view says that we already have an existence proof for how to scale systems: it just requires data and compute. The hard part is creating intelligence, and you can iterate faster if you have a simple, concrete benchmark because then you’ll be able to easily measure progress, and you’ll require less compute at each step. In this world, new, radically different approaches are developed to solve a challenge like ARC AGI, and then once there’s a solution, we just reintroduce the existing methods to scale it up. And to scale, you’d just have to figure out where you can plug in gradient descent. Now maybe plugging in gradient descent is easier said than done, but I don’t think that will be case: we’ve figured out a way to make it work for all sorts of different inputs, outputs, architectures, constraints, objectives etc. And I should also say: it might be the case that people should be working on an even simpler task than ARC — e.g. maybe the perception component is an unnecessary added challenge.

Now there are three different variations of this route. In one world, you solve intelligence and then scale it up directly: this is the right turn path. In the other, you take the lessons learned and apply them to the existing scaled up solution: this is the double ascent. In the third path, you solve intelligence, and then develop scale and intelligence in tandem from scratch: this is the hill climb. In the hill climb, you are still utilizing the lessons learned from solving intelligence, but perhaps it requires a decent amount of adaptation to get the same approaches to work at scale. I think it is quite likely the case that the double ascent just isn’t possible: I think the approaches that worked for scaling are a local optimum, and it will be difficult to reproduce the intelligent priorities when you have such strong priors from hours and hours of training on the whole Internet.

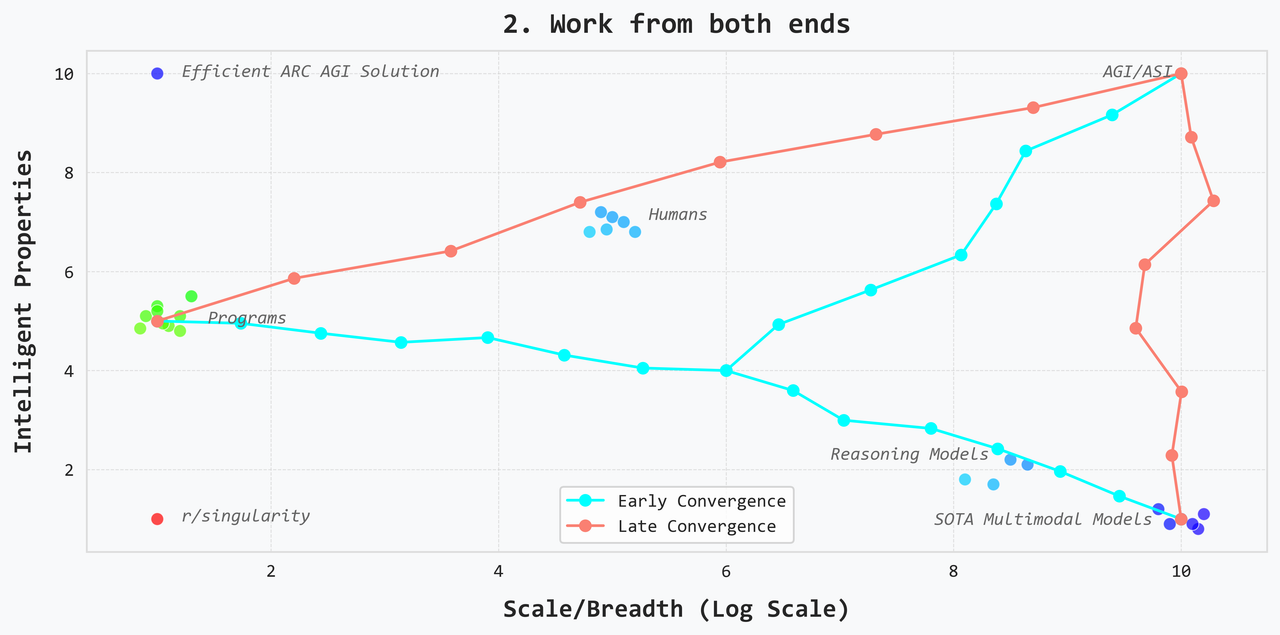

2. Work from both ends

This view is that you will get more progress if you try to add scale to intelligence while also adding intelligence to scale. There might be strong synergies where advancements in one path lead to advancements in the other. Or perhaps, working on both will serve as a form of validation: you discover methods by working on the small scale and then verify that they do actually work by trying to transfer them to the scaled up solution. I think while the intuition of working from both nodes is simple, it’s quite unclear what the actual path will look like. Perhaps the two paths will converge at some point. Perhaps they only converge at AGI. Perhaps they end up having some sort symmetry. In the end, the shapes of the paths don’t really matter as long as you are working from both ends because at a very simple level, if this was just another pathfinding problem, it would be hard to justify not trying to take advantage of both known nodes by searching from both ends.

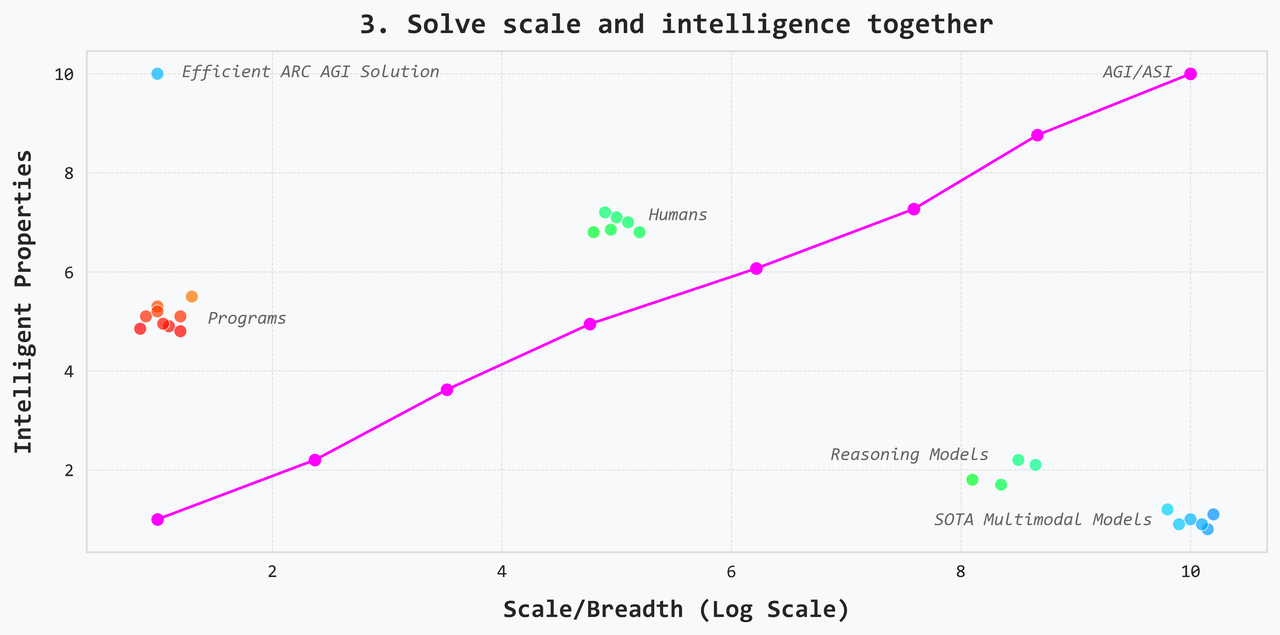

3. Solve scale and intelligence together

This view says that the way to develop intelligence is to work on a variety of tasks in a variety of domains i.e. you’ll only find new solutions if you work on new problems. This view has a decently strong basis in the development of humans and animals more broadly. This is not just the scaling hypothesis that has driven the last decade of research. It says that intelligence does not necessarily come for free with breadth: it must be actively selected for with very strong incentives, AND one must be willing to reject gains in breadth if they are not accompanied by gains in intelligence.

The path here might look like reinforcement learning from scratch (i.e. without relying on data for solutions) but still letting the model use code to solve problems. Train these models on a variety of tasks, and they’ll discover useful behaviors on their own as they progress to harder and more diverse environments. In order to achieve scale, data will almost certainly still need to be an important part of equation, but there’s a big difference between using data to create problems versus using data to provide solutions. While there is definitely some truth to the view that the SOTA models do use data to create problems (through self-supervised learning), I think it’s inarguable that the existing usage of data is much more geared towards providing solutions than creating problems.

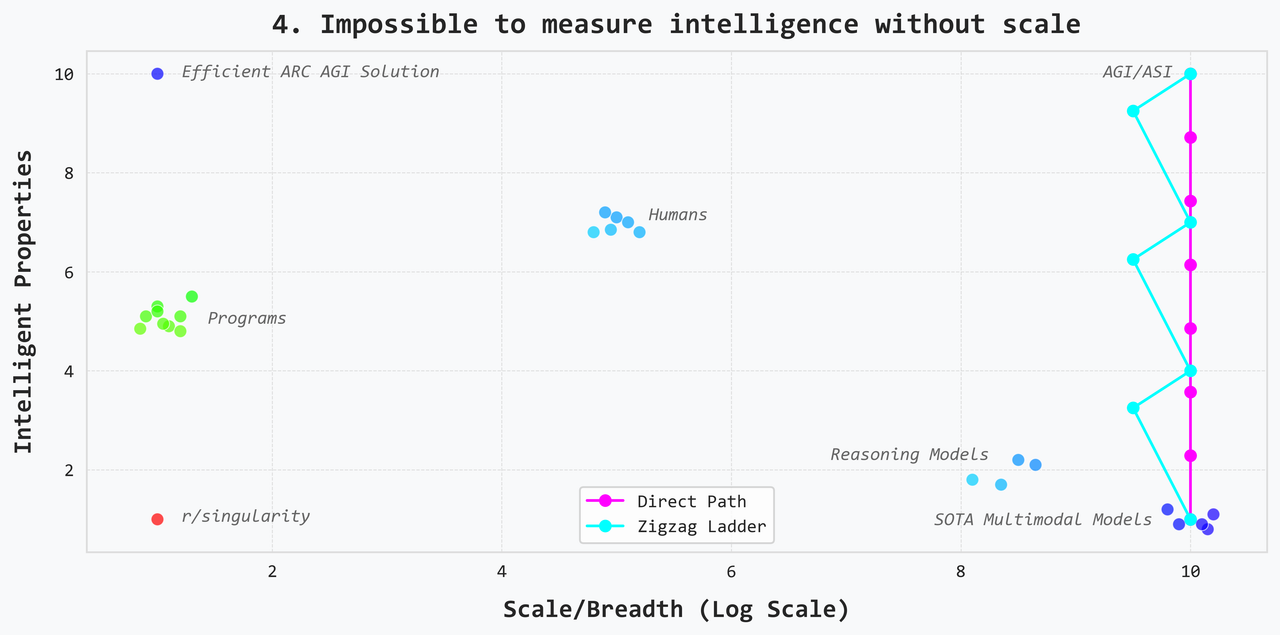

4. It is impossible to actually measure intelligence without scale

This view says that you can’t validate an approach on a single benchmark or a simplified, narrow problem: in order to see if a technique works, you have to test it out on every problem across every domain. A solution is real and scalable if and only if it works across the board. This view is related to the previous one, but it is more extreme and, in some sense, more stubborn. Part of the motivation here might just be an unwillingness to lose breadth — or perhaps, an unwillingness to lose customers. The only way to get off the ground if you’re testing across the board is to start from the existing scalable solution i.e. the SOTA multimodal models.

There are two versions of this approach: the first is the direct path, and the second is the zigzag ladder. In the zigzag ladder, you tradeoff some breadth for intelligent properties. Then you regain the scale and repeat the process until you have gained a whole lot of intelligent properties and maintained scale. This looks like the path the top labs are going down with reasoning models being the first step. I think it’ll be clear fairly quickly that this approach is very expensive — requiring a whole lot of engineering, experimentation, and labeling. And in particular, I think we’ll see that the work done on this front will be too niche and will not carry over well to different approaches — not even the direct path.

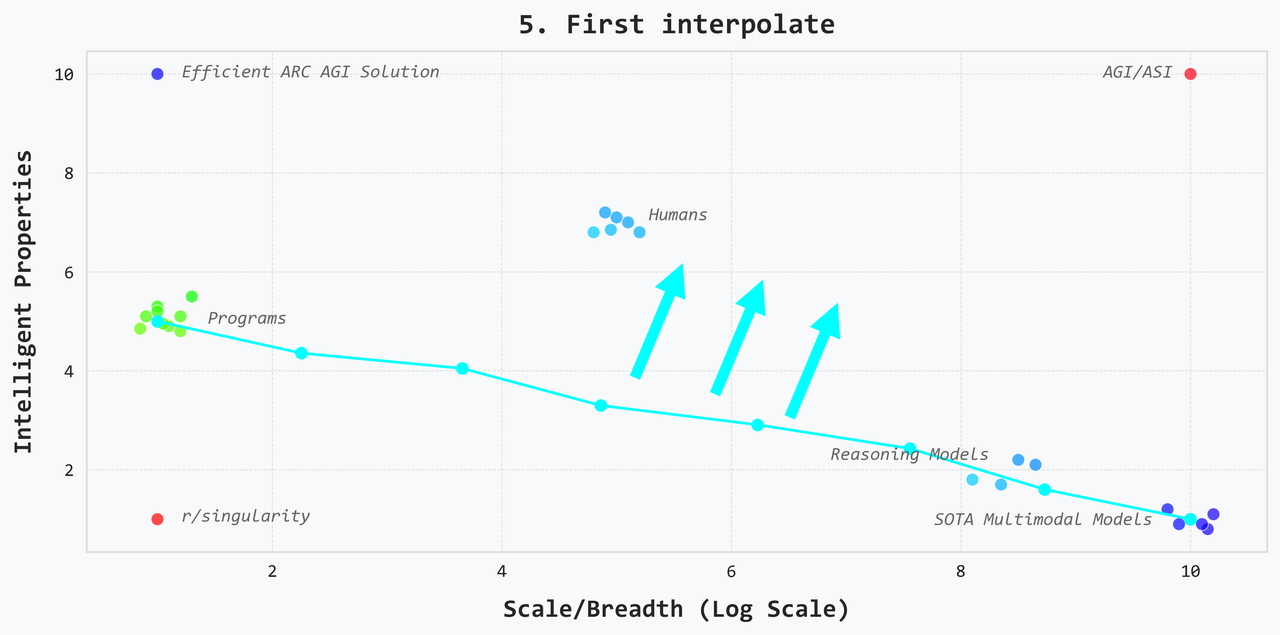

5. First interpolate

This view says that we have two existence proofs so instead of trying to discover something totally unknown that pushes the envelope, we should first establish a Pareto frontier for the tradeoff between intelligence and scale. To do this, you create many different systems that some combination of the intelligence of programs and the breadth of SOTA models. Once we’re able to bridge the gap in a meaningful way and also concretely understand the tradeoff (i.e. the shape of the Pareto frontier), then we can start pushing the boundary and moving towards systems with high intelligence and large scale.

6. Another one

I don’t know: I’m sure there’s some other view that suggests a spiral path or an ouroboros or something lol.

Final Thoughts

Anyway, I think there’s some case for each of these perspectives, and I do think it’ll become clear that different organizations have started going down different paths. My own view is somewhere between the first and second views but leaning towards the first. I think as long as you’re working on a sufficiently general problem, the advantages of working a lighter problem are just so clear. And I do think ARC AGI pretty clearly fits this bill. At the same time, it’s really hard to argue that you wouldn’t just benefit from searching from both nodes. I think this is also maybe the most pragmatic approach since working from both ends will allow the SOTA models to continue delivering new value to customers. I don’t expect leading labs to really commit to intelligence until after the bubble bursts, but there will still be clear and powerful use cases for the SOTA models at this point.

On a personal level, it’s been difficult to get much done on my own when I’m also working a full time job and don’t have a cluster. But I also think part of the problem is that I have a bunch of different ideas that I still find very interesting but don’t really build to one thing. Given this, I’ve leaned towards reading and writing a lot more than coding and experimenting. I think that with this post, I now have this sort of grand unifying vision, and it’s good motivation to work on ideas that require less compute — even if they’re occasionally kind of boring. I’m going to try to actively avoid writing — or at least publishing — going forward because it does take fucking forever.