This was originally a post about a visualizer I made; that original post is available below. The day after I started thinking about the conjecture in an inverted way, which led to this addendum.

Addendum: An Inverted Perspective

There’s another way to look at the conjecture: by sequence length. If \(X_i\) is the set of all numbers with a Collatz sequence of length \(i\), then we start with the base case of \(X_0 = \{1\}\), and we can build \(X_{i+1}\) by extending \(X_i\). For all \(x\), there’s two numbers that could have led to \(x\): \(2x\) and \(\frac{x-1}{3}\) (this is just inverting the Collatz rule). The first one always applies, but the second one only applies if \(x\) is even and equal to 1 mod 3 (if \(x\) was odd, then \(\frac{x-1}{3}\) would be even, and we wouldn’t apply the \(3n + 1\) rule).

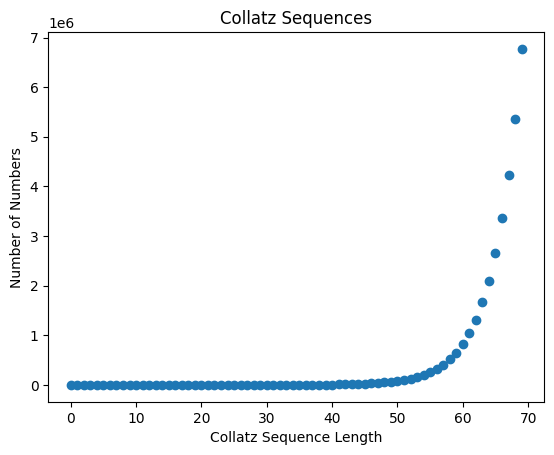

This perspective gives us a few things. First, we have a maximum value for numbers with sequence length \(i\). Using the inverted rule, we are at most doubling on every step, so the max is just \(2^i\), and we do always obtain this max. Second, the dynamics of how these sets grow is a bit easier to see. All elements in \(X_i\) will correspond to at least one element in \(X_{i+1}\) cause you can always apply the doubling rule, and some will correspond to a second element if/when it meets the requirements. This also gives us bounds on the growth of the sets: it’s at least constant and at most \(2^i\) (alright so not the tightest bounds). In practice, the curve is definitely an exponential with the base very slowly converging to something like 1.2637. Another important factor in the dynamics is the fraction of the set that is even vs odd, since the second rule only applies if \(x\) is even. One might naively say that of the even elements, a third of them are equivalent to 1 mod 3. This actually appears to be true in practice.

Ok, so now suppose that we actually have a stable system with stationary distributions. Let \(\alpha\) be the share of elements in \(X_i\) that are even. All of the even elements in \(X_{i+1}\) must come from applying the \(2x\) inverted rule, and all of the odd elements from applying the \(\frac{x-1}{3}\) inverted rule. We can always apply the first rule, so the number of even elements in \(X_{i+1}\) is \(|X_i|\), and (if the fraction really is just \(\frac{1}{3}\), then) the number of odd elements is \(\frac{1}{3}\alpha|X_i|\). Thus if the proportions for even to odd are stable, then \[\frac{\alpha}{1-\alpha} = \frac{|X_i|}{\frac{1}{3}\alpha|X_i|} = \frac{3}{\alpha}.\] Cross multiplying and rearranging yields the quadratic \(\alpha ^ 2 + 3\alpha - 3 = 0\) which has a solution at around 0.7913. Recall that this is the fraction of the set that is even. From this we can derive the growth ratio: \(1 + \frac{\alpha}{3} \approx 1.2638\), which lines up with empirical rate.

This gets us back to the most annoying thing about the conjecture. No matter how you look at the conjecture, it is easy to prove that there are infinitely many positive integers for which the rule applies, but that’s not enough to say that it applies for all positive integers. After all, there are infinitely many odd numbers, but not all integers are odd.

On the other hand, this might look like evidence that it doesn’t apply for all positive integers: the max value of elements within length \(i\) is \(2^i\), but we only have something like \(1.2638^i\) elements in \(X_i\), so the fraction is actually getting sparser and sparser as \(i\) increases. This is still coherent, however, with the conjecture because the “missed” elements just have longer sequences: they’re not actually missed. 5 doesn’t have a sequence of length 3 (recall \(5 \leq 2 ^ 3 = 8\)), but it does have a sequence of length 5 (5 → 16 → 8 → 4 → 2 → 1). Alright well, hope this was interesting.

The Visualizer (Original Post)

I’ve been playing around with the Collatz conjecture. I wrote up this visualizer after noticing how nice the binary representation is. That’s the main point of this post. I also did some data exploration yesterday here and here. I feel like each time I look at the conjecture, I have some novel perspective, but the novel perspective just offers a fresh reason to say “Oh ye, this shit’s gonna be so hard to prove.”

I’d like to thank Github Copilot/Claude Haiku 4.5. This was my first time using it or any other AI coding tool directly in a codebase. I’ve always just used LLMs in the browser (so that I can largely control context), and I think I still largely prefer that workflow after today. There’s one major exception: styling. Copilot wrote all of the CSS for the site. CSS is by far my biggest weakness, and it’s the thing I despise the most about any web dev or GUI work. This project took the better part of a snowy day, but it would’ve taken much longer and ended up with a much uglier result if I didn’t have Copilot to do the styling. Early on, I almost rage quit over some stupid styling stuff, and I only kept going because I promised myself that I’d make Copilot do all of the styling entirely on its own.

Copilot’s autocomplete was also decent, and it wrote the JSX container logic for the bits, but it immediately broke whenever I tried getting it to do any more complex logic stuff, and I was pretty happy to write and engineer all of that myself. That said, I used up the entire Copilot free quota by the end of the day anyway. All in all, this experience has definitely made me much more amenable to web dev again.